Originally written for the University of Amsterdam and published on Medium.

In recent months, the 2024 Presidential Election, Boeing safety concerns, inflation, US Supreme Court, Israel-Hamas war, and former President Donald Trump’s legal battles have dominated the news cycle.

While these issues may widely be considered news “fit to print”, former broadcast meteorologist Chris Gloninger has labeled the extensive attention as “bad journalism.” To him, there is one topic that is missing that front page coverage as it continues to impact Americans in nearly every facet of life: climate change.

“The fact that we’re covering this circus in court every day and the next thing that Donald Trump says, is a waste of resources,” Gloninger said.

Gloninger, who worked as a meteorologist for nearly 20 years covering climate change primarily in the Northeast, is calling for a restructuring of how journalists give attention to the issue — no matter what beat they cover. Instead of being covered periodically — often as a scientific or environmentally heavy feature — climate change should be making headlines daily.

“They need to make time for it in this crazy news cycle, which they’re just not. And that’s local news, that’s national news, ” Gloninger said. “I just kind of, like, scream at the TV when I’m listening to everything and anything else that they’re covering, and when they shouldn’t really be covering that.”

Research has found that the news media, including meteorologists, carry a great deal of influence when it comes to shaping belief about climate change. Other studies have indicated that by increasing belief and concern regarding the issue, individuals may be more likely to embrace initiative behaviors looking to curb the effects of climate change. This makes coverage of the issue all the more important.

Meteorologists (left to right) Jeff Berardelli, Lauren Casey, and Chris Gloninger share their opinions on how climate change reporting has evolved and where it should be today

WIDESPREAD IMPACT

For decades, coverage of climate change has been pigeon-holed to the science section of the newspaper, often only making an appearance on the front page when connected to national or global politics or mass fatalities caused by extreme weather.

This categorization may make sense for some, as climate change is regularly discussed as a data-driven topic, with stories filled with statistics, comments from scientists, and graphs explaining changes in temperatures or other weather anomalies.

However, climate change is not just a scientific issue with experts pointing to a direct impact it appears to have on daily lives.

In the lower 48, the 2023/2024 winter was found to be the warmest on record, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Shockingly high temperatures resulted in near-record-low snowfalls, intense flooding, increased rainfall and shorter lake freezes.

The 2024 summer has also already seen record-breaking heatwaves, putting millions of Americans at risk. These temperature anomalies are being recorded across the country, with dozens of major cities like New York, Washington D.C. Phoenix, Chicago, and Portland seeing temperatures several degrees higher than what is considered to be normal.

Source: Climate Central

Scientists agree that these major weather changes are being driven by climate change. The effects are becoming more frequent and intense, largely due to humans’ negative contribution to the warming atmosphere.

Not only do these effects of climate change have greater impacts on human life and wildlife in the US, but it negatively impacts areas that financially rely on winter tourism for skiing, ice fishing, skating, and more.

It doesn’t stop there. Hundreds of athletes worldwide have pointed to rising temperatures and increased air pollution having a direct negative impact on their health and performance. In many parts of the US, public buildings such as schools and libraries were built to withstand cooler temperatures without air cooling systems. Now, record-breaking heat has forced dozens of schools to close to protect students and staff.

Jeff Berardelli, the Chief Meteorologist and Climate Specialist for NBC affiliate WFLA, emphasized that coverage of climate change is vitally important for Americans today, as the effects of climate change are only expected to get worse.

“Everything’s gonna get tougher, and eventually it’s going to lead to a lot of instability and probably a lot of conflict,” Berardelli said. “This is why climate change is so dangerous. It’s not the one storm. It’s not the one heatwave, it’s how it’s all going to come together to make life really challenging.”

Experts with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have warned that excessive energy use, land-use, individual waste, as well as increased consumption of mass produced products and the transportation needed to supply these goods are contributing to increased emissions of greenhouse gasses.

“We are witnessing what is by far the fastest changing climate that we’ve seen potentially in millions of years, and that it’s being done by us,” Berardelli siad. “The changes are fairly extraordinary and every year that goes by, it’s proven to be even probably more impactful than we thought it would be.”

CHANGING COVERAGE

While many meteorologists are unhappy with the way climate change is covered today, it is dramatically different from the coverage that existed in the early 2000s — if any.

Berardelli, who has worked in meteorology for over 27 years, revealed that there was very little coverage or even discussion about climate change within the field at the time. Those who studied meteorology were exposed to information about the issue including studying warming temperatures in college, confirming climate change was real. However, Berardelli said there wasn’t much data meteorologists could use easily in their reports.

“There wasn’t much of anything going on back then,” he said, explaining that now, most media organizations have scientists who are able to produce detailed graphs and illustrations breaking down confusing information.

“Back then, it was just polar bears on ice,” Berardelli said.

Lauren Casey, an Emmy-award winning meteorologist, started working in broadcast in 2006. She agreed that in the early 2000s, not many people — meteorologists and other journalists alike — were covering climate change.

“Climate wasn’t even really a topic at all that people were talking about in the media back then,” she said. “And then it started to slowly build up.”

Casey didn’t attribute one specific moment for the surge in climate change coverage, instead calling it a “slow build.”

She pointed to a number of factors including public perception. As viewers and readers became more open to discussing and hearing about climate change, Casey said media organizations followed suit.

Previously, these organizations, both local and national, tended to steer away from contentious topics like climate change due to negative feedback targeting the journalists or networks themselves. Gloninger claimed that by doing this, networks were catering to small percentages of the population that have long wanted nothing to do with climate change, often failing to believe in its existence.

“I think it’s crazy to cater newcasts to that small minority,” he said. “You lose your journalistic integrity, and honestly, that’s journalistic malpractice when you’re allowing an audience to dictate what shouldn’t be covered.”

The 2016 Presidential Election gave this minority a larger voice, Gloninger explained, as Trump ascended to office and perpetuated skepticism on clean energy initiatives while repeatedly calling climate change a “hoax.”

Like other social issues like education and abortion, experts agree the polarization and politicization of climate change escalated during the election and rise of misinformation. With distrust becoming more apparent, meteorologists and environmentalists began pushing back.

“During the Trump administration, because there was so much pushback against environmental regulations and climate communication, I think probably the public rebelled a little bit,” Berardelli said. “If people don’t think that the problem is being addressed, it gets them angry and it raises public concern, and then when people think it’s actually being addressed, or maybe being addressed too much, they switch their priorities.”

As a result, Casey said there was an “exponential” surge in coverage of climate change, particularly within the last five years.

CLIMATE MATTERS

Some of this growth can also be attributed to increased access to information regarding climate change and its effects.

In 2012, the nonprofit Climate Central launched a program called Climate Matters, offering up weekly reporting materials for meteorologists and journalists to use. At the time, only a dozen TV meteorologists participated in the program — but it was quickly a success.

“Before climate matters, there would have been very little that I could have shown on TV without a tremendous amount of time and effort on my part of compiling data…it just wasn’t possible,” Berardelli said.

Research has since found that when using the materials, viewers were more inclined to believe that climate change is indeed happening, is primarily caused by humans and has detrimental risks.

Now, more than 3,000 meteorologists and journalists in over 200 locations across the U.S. participate in Climate Matters, using weekly materials to better make sense of confusing data for viewers.

Casey, who now works as a meteorologist for Climate Matters, said the use of these materials has allowed other meteorologists to develop “incredible” broadcasts and articles covering climate change.

One tool Casey is currently working on to better assist journalists in their coverage is a climate shift index, which calculates how much of an impact global warming has had on daily temperatures as well as high and low average temperatures across the world. The index provides visual outputs, allowing meteorologists to share already developed images in their broadcasts, saving them time and money.

Casey explained this can help journalists “try to get people to understand that climate change isn’t some nebulous future thing, like climate change is in your backyard right now impacting your temperatures.”

DROWNED OUT

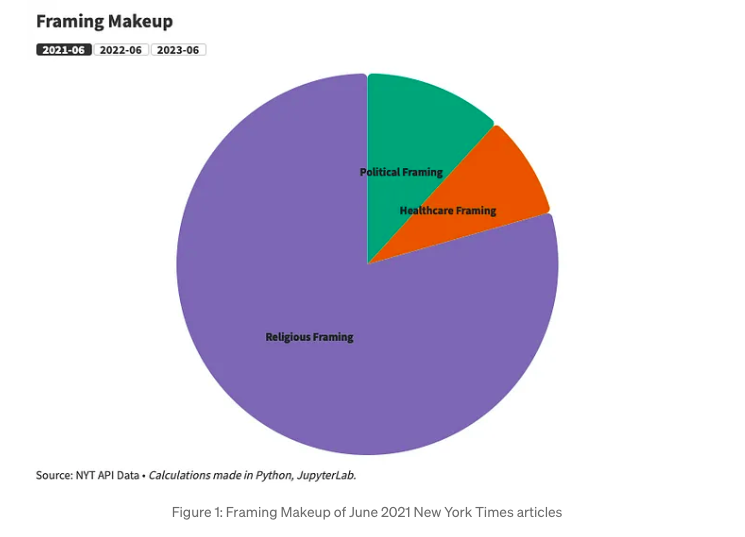

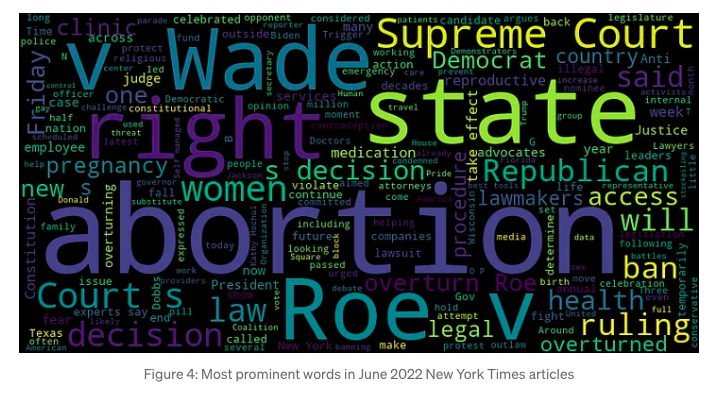

As climate change has become more socially relevant, there is evidence of the issue gaining more attention in the news media overall.

Looking at the New York Times alone, the amount of headlines that feature the phrase “climate change” increased by more than 2,000% between 2010 and 2021. The number of headlines featuring the words “carbon emissions” doubled in the same timeframe. Though, it is worth noting that the appearance of the phrase “global warming” decreased by 20%.

The Fall 2023 Yale Program on Climate Change Communication quarterly survey also found that around half of Americans — 51% — have said they hear global warming discussed in the media at least once a month. Around 28% said they hear global warming is discussed at least once a week, while 8% said they never hear it mentioned in the media.

While there is increasing relevance, the issue does still appear to be drowned out by other topics.

In 2010, only six headlines from The New York Times featured the phrase “climate change.” This jumped to 102 in 2020 and dropped back down to 72 in 2021. While this is massively higher than 14 years ago, it has remained lower than other political and foreign topics like Ukraine and Joe Biden.

INTERCONNECTED REPORTING

Given the prominence of other topics, there comes the issue of determining the best way to increase coverage of climate change.

Meteorologists and scientists appear to all be in agreement that climate change has some influence on beats like politics, healthcare, the economy, food and drugs, sports, and more. Therein, some are suggesting the issue should be further integrated into non-typical climate reporting.

“It covers everything,” Gloninger said. “And no matter what beat you’re on, you should be finding a way to cover it. I mean, it’s hard to help. It’s tied to politics, it’s tied to schools, it’s tied to sports.”

Berardelli admitted that covering the issue can be quite difficult, but said that journalists should seek to “match the moment” by leaning on how “interconnected” climate change is with other issues.

For example, when discussing food scarcity and rising food prices, journalists typically lead with impacts of inflation. These reports can go a step further by pointing to difficulties in producing the food at all due to recent droughts, floods, or heat waves caused by climate change.

Berardelli has seen this type of coverage in action and was thrilled to see reporters “finally telling people what it really means.”

“Things are gonna cost more, and there’s going to be more competition for goods that people rely on,” Berardelli said. “Everything is going to cost more and it’s going to create conflict…it’s going to create power struggles for resources. This is what climate change really is.”

Casey agreed that it is vitally important for Americans to know how climate change is going to impact their lives, their families and their communities. But, not all hope should not be lost when reporting on climate change.

Not only should coverage touch on effects of climate change like droughts, flooding, and warming winters, but it should highlight adaptive behaviors that may help mitigate future impacts.

Casey pointed out that even solutions like increasing green spaces and tree canopy in neighborhoods have been found to improve air quality, reduce crime, and increase mental health.

For her, climate change reporting should help motivate readers and viewers to take action.

“I’d love to see us talk about adaptation measures, and hopefully inspire people to demand more from their city, local, county, state, and national governments to provide this,” she said.

Whether the coverage is focusing on adaptive behaviors or the impacts of climate change themselves, Gloninger has emphasized that it should no longer be up to just meteorologists and environmental journalists to provide impactful reporting.

Instead, reporters in all beats should be looking for out of the box ways to integrate the topic into their work.

“I think really, the only path for climate journalism is making sure that it’s a collaborative collective action,” he said.

“It needs to be for us to make any difference at all in this issue.”